A Connectivity Case Study in Saarbrücken, Germany

Saarbrücken is a German city along the French border with a population of around 176,000 residents. Like most German cities, Saarbrücken’s core is a mix of walkable streets, urban buildings, and historic sites. Despite this, city leaders and residents are concerned about the future connectivity, mobility, and livability of their city.

A recent article in the local newspaper appeared under the title “Without Resolve There Is No Future,” lamenting the automobile’s takeover of the city in recent decades and the lack of planning for the future. Now, for the average American city, the article’s commuter statistics would be a dream: 4% ride bikes, 11% carpool, 17% use public transportation, 23% walk, and 45% drive to work alone. In contrast, over 75% of Americans drove to work alone in 2013. For a comparison, Saarbrücken’s numbers are similar to much larger American cities like Philadelphia or Seattle.

Now leaders are engaging citizens to create a 2030 Transportation Plan. The plan will cover six major goals, including fostering sustainability through public transit and cycling, accessibility, livable streets, and safety. But this isn’t the city’s first initiative to create a more livable city. Here are five ways Saarbrücken has been promoting connectivity in the past two decades:

1. The Pedestrian is [Becoming] King

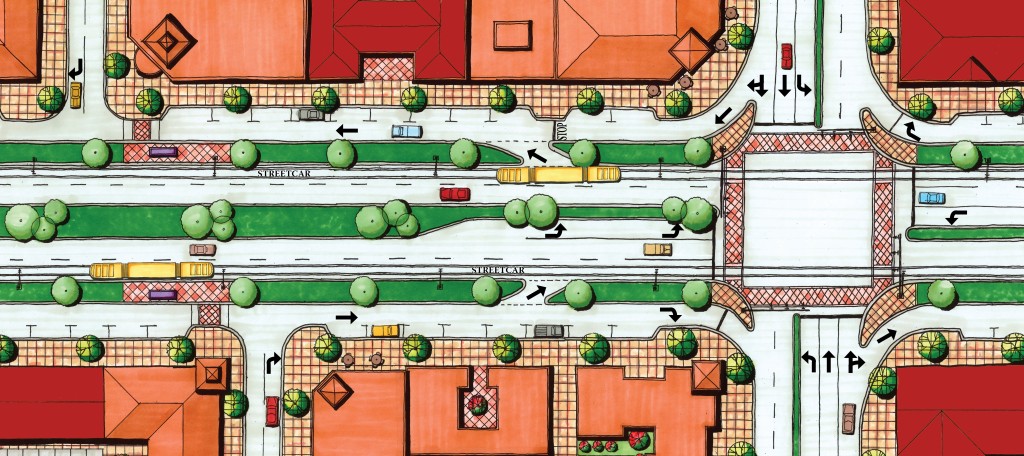

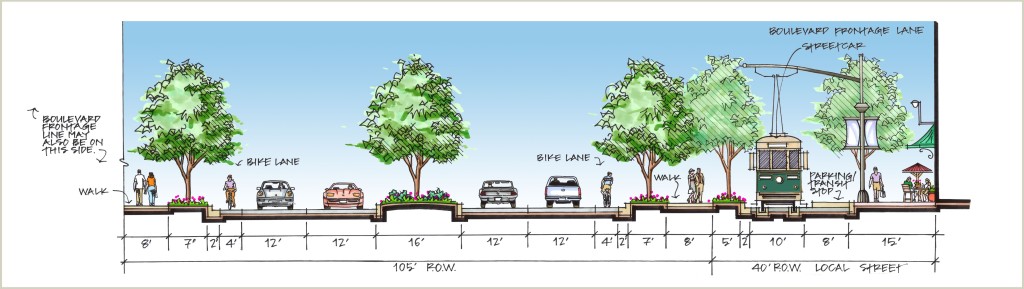

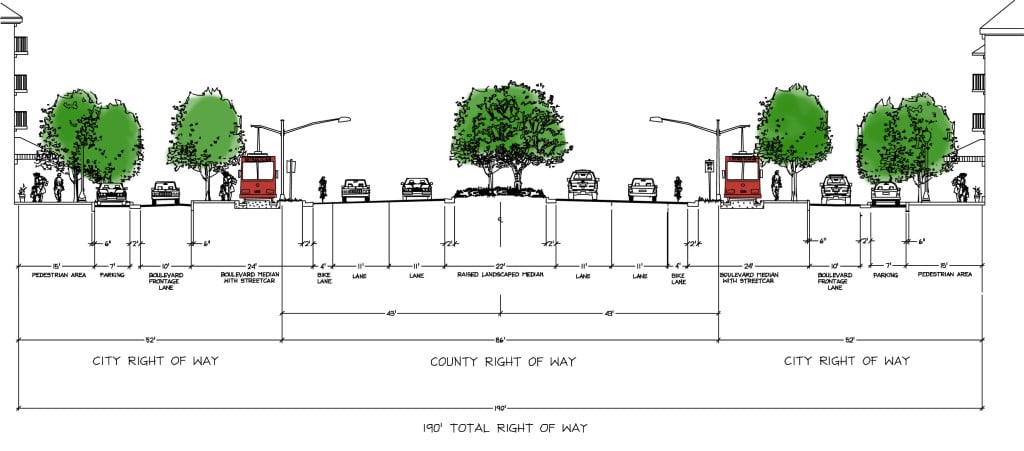

Saarbrücken’s main commercial corridor, the Bahnhofstraße, saw multiple incarnations in the past century. Bustling dirt roads with horse-drawn carriages gave way to streetcars in the 1890s. Then, after a nearly complete destruction during World War II, Saarbrücken’s main drag slowly reemerged in the 1950s and ’60s. But shiny new buildings weren’t the only difference along the Bahnhofstraße. By 1965, cars and diesel busses had completely replaced the extensive network of streetcars. For the next 30 years, the Bahnhofstraße looked like many American cities’ main streets: narrow sidewalks, angled parking, and a constant stream of cars.

A big shift came in the 1990s with the first pedestrianization efforts. Today, the entire length of Saarbrücken’s Bahnhofstraße (about one mile) is reserved solely for pedestrians. This effort continues today, with many side streets being converted into Woonerf-like pedestrian- and bike-friendly environments.

2. An International Streetcar

Although Saarbrücken’s streetcar system closed down in 1965, the Saarbahn revived the former Line 5 in 1997 as Line S1 and has seen multiple extensions since then. Today, this “regional streetcar” serves 40,000 riders per day at 43 stations and runs over 27 miles through Saarbrücken and various smaller cities. The core is served at 7.5-minute intervals, while farther out neighborhoods and towns are served in 15-, 30-, and 60-minute intervals. What makes the Saarbahn special is that its last stop, Sarreguemines, lies in France, making it not only a regional but also an international streetcar.

3. Bike Parking

While only 4% of Saarbrücken commutes by bike, bike parking can be found throughout the city. With a goal of getting at least 10% of commuters on bikes in the next few years, bike parking and cycle tracks are a major part of future transportation plans.

4. A Multi-Modal Waterfront

While the Saar river is the namesake for, well, just about everything in Saarbrücken, the riverfront itself seems to have been an afterthought in the Bahnhofstraße renovations of the 1950s and ’60s. That changed in the past year, however, with the project Stadtmitte am Fluss, or City Center on the River. With updated lighting, renovated storefronts, upgraded accessibility, and new greenspaces, the city hoped to activate a neglected portion of its downtown waterfront.

While the project was met with skepticism over costs and necessity, it was completed successfully and has brought new life–and connectivity–to the city’s core. An improved multi-modal trail connects existing riverside paths for a great walking and biking network.

5. Saarbrücken: A City to Explore on Foot

With all the pedestrian streets mentioned above, it’s no surprise that 23% of Saarbrückers commute on foot and that the streets are always filled with shoppers. Smaller initiatives, however, have played a big role in getting people out of their cars. For example, sidewalks have been widened, directional signage with walking distances is commonplace, underground shopping tunnels allow pedestrians to avoid crossing large streets, an existing historic building was converted into a mall in 2010, and café seating spills out onto sidewalks throughout the city.