Single-Family Can Be Urban, Too

American housing design is in need of a paradigm shift. Recognizing generational preferences, increasing affordability constraints, and sustainable solutions are needed to start a new chapter in the planning of our cities, especially when it comes to housing. But that doesn’t mean the single-family home is dead. In fact, if we begin to build houses around the principles of density, efficiency, and flexibility, a modern version of the single-family home could bridge the gap between what incentivizes builders and developers, and the new reality faced by many potential homebuyers.

Seattle, 1947. Photo © Seattle Municipal Archives

Seattle, 1947. Photo © Seattle Municipal Archives

The nation’s changing demographics are a driving force behind a new focus on the often overlooked needs of two explosive market segments: singles in both Gen Y and Baby Boomer cohorts. With over half of all American adults single1, it’s no surprise that 28% of new-home buyers (18% women and 10% men) are single2. Additionally, Generation Y (now between 20 and 34 years old) and Baby Boomers (currently between 50 and 68 years old) make up nearly two-thirds of homebuyers3. While the housing industry has begun looking at the opportunity to serve Baby Boomers, it often fails to completely understand the needs of Gen Y and single buyers.

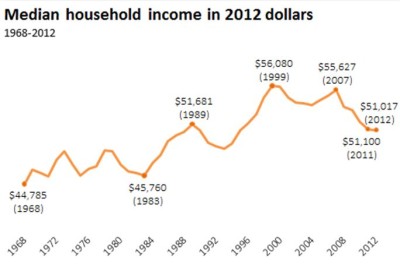

While three-quarters of Americans across all cohorts still prefer to live in single-family detached homes4, it has become difficult for Gen Y and single buyers to find affordable, tailored homes in the current stock of home designs and builder offerings. Financial pressures are increasingly affecting young homebuyers’ decisions. Adjusted median household income has remained virtually unchanged since 19895 and is one of the factors behind increased credit card debt and high student loans. Combined, stagnant earnings and growing personal debt are reducing the buying power of many young Americans, which is reflected in a 12% drop in first-time homebuyer market participation in the past decade6. Because the conventional building model does not take these restrictions into account, it misses out on a large portion of potential homebuyers.

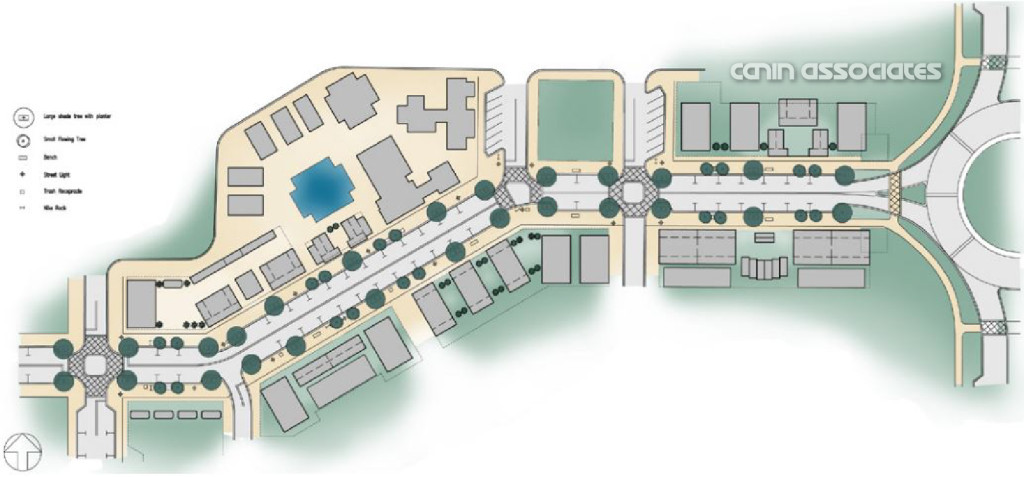

Changing demographics, increasing financial constraints, and modern preferences create the perfect springboard for a new era of very different single-family offerings. For example, without losing the quality and appeal of a traditional single-family community, micro homes (under 1000 sq. ft.) can create neighborhoods of truly detached single-family homes at densities of over 20 units per acre. For builders, higher densities can mean lower land costs per unit; for developers, micro neighborhoods can yield significant margins in per-acre sales; and for buyers, the ability to afford a detached home can once again become an aspirational reality.

In our site planning tests, we found that micro neighborhood designs can fit between four and six specially-designed homes (ranging from 500 to 900 square feet) onto a quarter-acre lot, allowing for densities of 16, 20, or even 24 units per acre. This model gives developers the ability to create complete, intimate neighborhoods. By limiting the size of the offerings to no more than 20 to 30 homes per neighborhood, it becomes possible to drive rapid absorption by matching demand and opportunity on a finely calibrated scale. Developers can create a sense of buyer urgency with flexible pricing that they can adapt to demand, available inventory, and market pricing.

With diversifying preferences and changing economic conditions, increasing residential density is the next logical step in American home design for builders, developers, municipalities, and, most importantly, buyers. By adapting the single-family home to a more urban context, we can take these considerations into account and create walkable, authentic communities.

Sources:

[1] Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2014

[2] National Associates of Realtors, Profile of Home Buyers and Sellers, 2011

[3] National Association of Realtors, Home Buyer and Seller Generational Trends, 2014

[4] National Association of Realtors, National Community Preference Survey, 2013

[5] US Census Bureau, 2012

[6] National Association of Home Builders, Wall Street Journal, 2014