A Vision for Mercy Drive

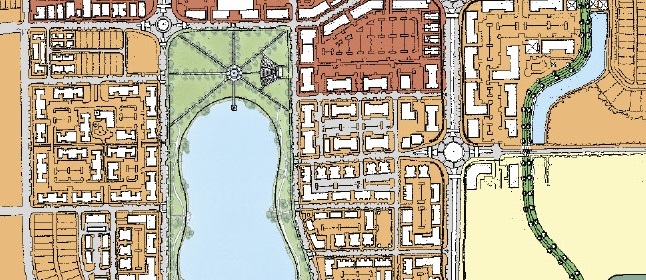

Hidden behind the Central Florida Fairgrounds and nestled between College Park and Pine Hills, Mercy Drive is a predominantly African-American community with a unique mix of single family neighborhoods and a variety of large and small apartment complexes housing moderate and low-income families. Additional pockets of commercial, industrial, and institutional development are scattered along its main street, Mercy Drive, as well as some recreational uses such as the City of Orlando owned and operated Northwest Community Center.

The community has had its challenges, ranging from traffic concerns to the closure of several poorly maintained apartment complexes that are now in City ownership. Limited transportation connections in the area make Mercy Drive a popular cut through, especially for freight truck traffic from the nearby industrial properties.

Recognizing the need for a unified visioning approach, and under the leadership of Commissioner Regina Hill, the City retained Canin Associates to work with the residents and stakeholders to create a forward-looking Vision Plan to improve the community’s quality of life and bring out residents’ talents to build a better future for their families and their community.

“A safe, attractive, and connected community with quality homes and apartments that empowers neighbors of all ages to learn, build, and create together.”

-Mercy Drive Vision Statement

The visioning process kicked off with over 100 residents and stakeholders in attendance at the first of three public meetings to be held within the community at the Northwest Community Center. After analyzing the information gathered from the first meeting as well as from an area-wide walking audit, expert interviews, and a housing conditions assessment, a second public meeting was held to present a vision statement as well as physical design and community building concepts. Residents and stakeholders then voted on which of the concepts they thought were most appropriate for their community’s future.

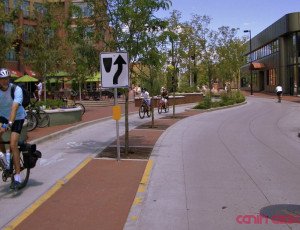

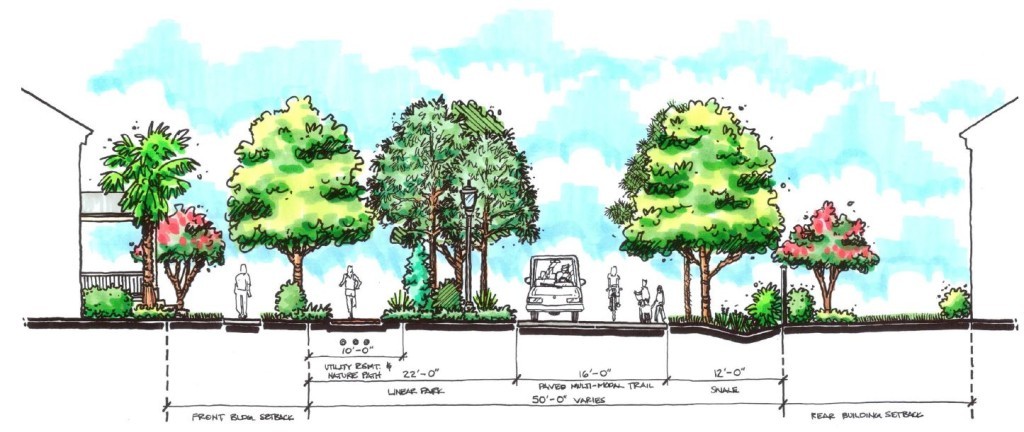

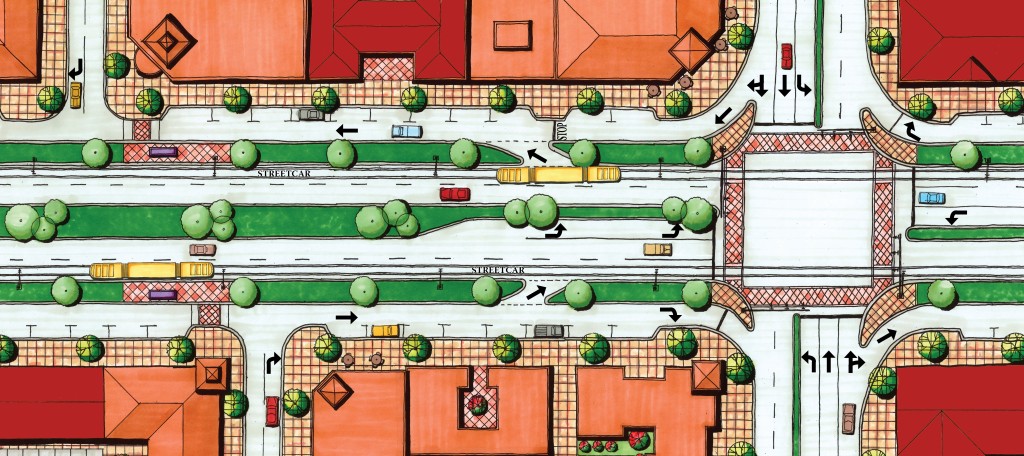

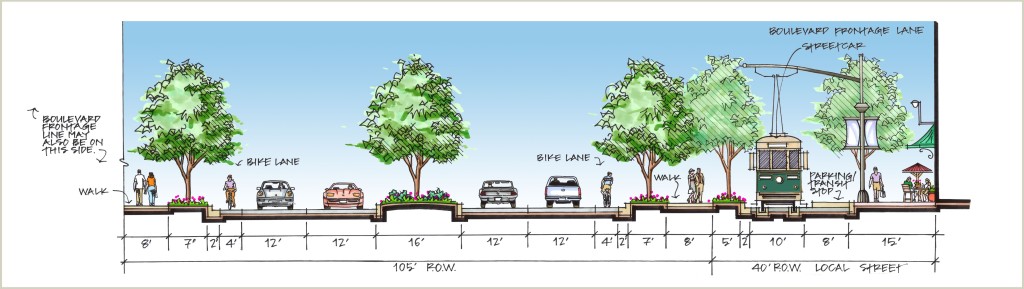

The design concept that received the most votes was a multi-use neighborhood center that provides public gathering space along with new commercial and small business opportunities. Streetscape enhancements to help mitigate traffic issues, improve walking and biking, and provide community gateway features came in a close second place along with ideas for new higher density single-family housing opportunities on a couple of City-owned parcels.

The community building programs that received the most votes were focused mainly on home maintenance, such as a tool lending library and home repair classes, as well as increasing community-wide events, some of which could even include partnering with the Orlando Police Department.

With the community’s priorities determined, a vision report was produced that will help guide both public and private investment for current and future Mercy Drive residents. The executive summary of this report was distributed during the third and final public meeting, which was in the form of a community resource fair. This final meeting brought multiple city departments, third party organizations, and more into the Northwest Community Center to engage with residents and stakeholders, and to help begin the process of realizing their community’s new vision.

Canin Associates is proud to have partnered with the City of Orlando and Mercy Drive residents and stakeholders in developing the vision for their future. We look forward to what will be coming next for this high-potential community!

Visit the City of Orlando’s project page for access to the final vision report documents and additional information.